Finding the Rosetta Stone

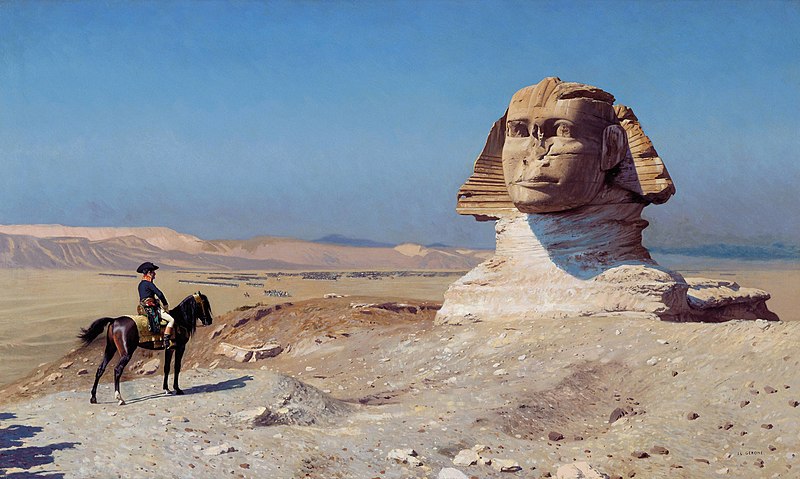

During the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt in 1799, French soldiers were strengthening the defences of a fort at Rosetta, now Rashid, in the Nile Delta. They uncovered an unusual stone with strange markings that had been used as part of the fortifications.

Their officer, Pierre-François Bouchard, ordered the men to stop work. He sent the stone to Alexandria for further examination.

Napoleon had brought a council of scientific and technical experts with him on the campaign. What they saw astounded them. The stone was a stela, an inscribed rock slab used for commemorative purposes by the ancient Egyptians.

It bore three versions of the same decree.

The top section was written in hieroglyphs, a writing system that used pictures as signs. The middle section was written in demotic Egyptian. Both were dead languages and undecipherable.

But the bottom text was written in ancient Greek, which scholars could read.

They realised this could be the answer to what had become known as through history as the riddle of the Sphinx – the key to translating ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The riddle of the Sphinx

In 1801, after the French surrender to the British in Alexandria, a dispute arose over the fate of the Egyptian artefacts that the French had found. Napoleon’s general, Jacques-François Menou, refused to hand them over.

It is not clear exactly how the stela eventually made its way into British hands. Apparently it was carried out of Menou’s residence in Alexandria wrapped in carpets and put on the back of a gun carriage. It went to England aboard a captured French frigate, landing in Portsmouth in February 1802.

Finally, the scholars could get to work.

But it was another twenty years before they made a breakthrough.

Thomas Young, an English physicist, was the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the stone denoted a royal name: Ptolemy.

A French scholar, Jean-François Champollion, subsequently concluded that hieroglyphs recorded not the words, but the sounds of the language.

With his knowledge of the Coptic language, which derived from ancient Egyptian, Champollion began for the first time to read and understand ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

So what is the Rosetta Stone?

We now know the Rosetta Stone is a decree, passed by a council of priests, affirming the royal cult of the 13-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation in 196 BC.

Securing the favour of the priesthood was essential for the Ptolemaic kings to retain effective rule over the populace, and the young king needed their active support.

How did it end up as building rubble?

Ruined Egyptian temples were used as quarries. The Mamluks had used it to shore up the walls of their fort in the fifteenth century.

And the three languages?

The Ptolemy government spoke Greek, and the priests used hieroglyphs, but the stone included text in low Egyptian to show its connection to the common folk.

Where is the Rosetta Stone now?

The Rosetta Stone is not especially significant as a single artefact. It was mass produced, and other stones have since been found that are better preserved. The prototype text was composed about a century earlier. Dates and names were changed for succeeding rulers.

But the Rosetta was the first stone to be unearthed. It is today one of the most famous objects in the British Museum.

You can see it in the Egyptian sculpture gallery, only now it’s behind glass to protect it from grubby hands.

Apparently, it has Napoleon’s fingerprints all over it.

If you love historical thrillers, you may like my best-selling series.

🔗 Grab your copy here on Amazon in Kindle ebook, paperback or Kindle Unlimited.